Fuel-Cooled vs. Air-Cooled Oil Coolers in Aerospace

In high-performance aircraft engines, the lubricating oil absorbs intense heat from engine components and must be actively cooled to maintain optimal performance and prevent damage. Aerospace engineers typically employ two methods for oil cooling: air-cooled oil coolers, which use ambient air in radiator-like heat exchangers, and fuel-cooled oil coolers (FCOCs), which transfer heat from the hot oil into the jet fuel stream via a liquid-to-liquid heat exchanger.

In this article, we will examine the design, benefits, and drawbacks of each cooling method and discuss how aerospace engineers weigh these trade-offs when selecting an oil cooling solution for an engine.

Air-Cooled oil Coolers

An Air-Cooled Oil Cooler is typically a plate-fin or fin-and-tube heat exchanger that behaves much like a radiator on a car. Hot engine oil flows through a network of plates with external fins, and cool outside air is forced over the fins, either by the aircraft’s forward motion and ram air or by dedicated cooling fans or ducts.

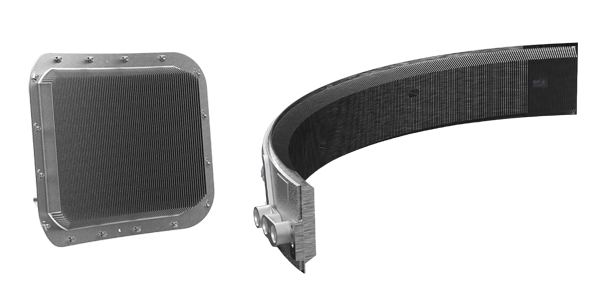

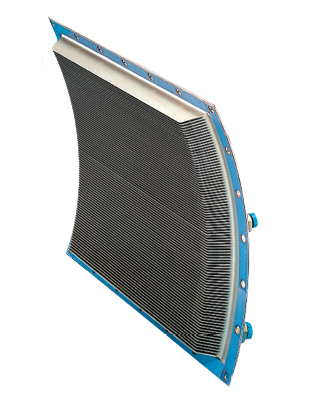

The heat from the oil conducts through the metal to the fins and then is carried away by the airflow. ACOCs can be standalone units mounted in strategic locations such as in an engine’s airflow duct. In some jet engines, surface coolers are used. These are curved ACOCs that wrap around the engine inside the cowling to maximize cooling surface area within a tight space. The construction is often lightweight aluminum plate-fin design for optimal heat dissipation and to withstand vibration and pressure of the oil system.

Advantages of ACOCs

ACOCs are part of the oil system only, not involving the fuel system. This separation means no risk of oil-fuel cross-contamination – a leak in an air-oil cooler will not directly introduce oil into fuel or vice versa.

ACOCs are cooled directly by the surrounding air. Ambient air is an effective coolant at high speeds and high altitudes, where air is cold. No additional energy is needed beyond existing airflow or a small fan. ACOCs perform well when the aircraft has sufficient air supply to the cooler.

ACOCs are field-proven. The concept of air-cooled oil radiators has been used since the early days of aviation. Modern ACOCs are highly reliable, built to withstand severe vibration, G-forces, and temperature extremes. They can be made fire-resistant and safe for engine compartments. Maintenance is straightforward and often limited to inspections for leaks or cleaning debris from fins.

Brick Surface Coolers

Typical Use Cases

Virtually all piston-engine airplanes use air-cooled oil radiators. Small general aviation aircraft have oil coolers mounted in airflow. These airplanes don’t fly high enough to need fuel heating, and keeping systems simple is best.

Many rotorcrafts use ACOCs for cooling engine oil and gearbox oil. They often integrate oil coolers with a fan or blown air system, because helicopters may not have significant ram airflow.

Auxiliary Power Units, small gas turbines usually in the tail of airliners, typically use air-cooled oil coolers. An APU runs on jet fuel but since it operates at relatively low altitudes, on ground or below 15,000 ft, it’s easier to use a compact air-oil cooler.

Some Turbofan engines use an ACOC in addition to the primary FCOC. Hughes-Treitler provided the surface air/oil cooler for the Rolls-Royce AE3007 Engines. This engine, used on regional jets and UAVs, benefits from a lightweight air cooler to maintain oil temps without an overly complex fuel cooling loop.

Fuel-Cooled oil Coolers

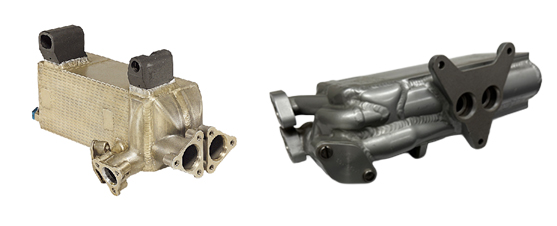

A Fuel-Cooled Oil Cooler is a liquid-to-liquid heat exchanger that ties into both the oil and fuel circuits of the engine. Hot engine oil flows through one side of the FCOC, while cold fuel from the aircraft’s fuel system flows through the other side in counter-flow. Because the fuel is typically much cooler than the oil, heat transfers from the oil into the fuel.

The now-warmed fuel continues toward the engine’s combustor and the cooled oil is pumped back into the engine. FCOCs are usually mounted on the engine or airframe near the fuel system for efficiency. The fuel flow through the FCOC is continuous whenever the engine runs, making use of the fact that large turbines pump far more fuel than needed, providing a ready heat sink.

Advantages of Fuel-Cooled Oil Coolers

Liquid-to-liquid heat exchange is highly efficient due to the good thermal contact and higher heat capacity of liquids. Fuel can absorb a lot of heat from oil without a large temperature rise because of fuel’s volume and flow rate. This makes FCOCs very effective at holding oil temperatures in check even under high engine loads. They can handle large heat loads in a compact package. A FCOCs efficiency doesn’t degrade at high altitude as air cooling might. The fuel is still available as a heat sink regardless of outside air density.

FCOCs also serve a dual purpose. They can not only cool oil but simultaneously warm the fuel. Warming fuel is desirable in high-altitude jet operations to prevent fuel freezing or formation of ice crystals/wax in fuel lines. Jet-A and Jet-A1 fuels can freeze around -40°C; feeding them through the FCOC ensures the fuel’s temperature rises before reaching engine fuel nozzles. This eliminates the need for a separate fuel heater, effectively combining two functions in one device. By optimizing thermal energy, FCOCs contribute to overall system efficiency. This also saves space and weight by combining the two functions in one unit.

Unlike an air cooler, an FCOC doesn’t rely on external airflow, so it doesn’t require additional inlets or protrusions on the aircraft that could cause drag. The cooling is all internal via fuel. This is beneficial for high-speed aircraft where minimizing drag is critical.

FCOCs tend to provide more consistent cooling performance from ground idle to cruise. If fuel is flowing, oil cooling is active. Air coolers, in contrast, might struggle in ground conditions with little airflow. FCOCs are thus very suitable for engines that experience a wide range of operating conditions and need reliable cooling in all phases.

Typical Use Cases

Almost all current high-bypass turbofan engines on commercial airliners and fighters use fuel-oil heat exchangers. Engines like the General Electric GE90, CFM LEAP series, Pratt & Whitney PW1000G all integrate FCOCs to manage oil temperature and preheat fuel. By using the cold fuel from wing tanks as a sink, these engines avoid large external oil coolers. Military jet engines, like those on the F-16, F/A-18, F-35, also rely on FCOCs because these jets operate across a huge flight envelope and demand the weight savings and fuel icing prevention that FCOCs provide.

Many turboprops and turboshafts that operate at high altitudes or in cold climates include fuel-cooled oil coolers. They often supplement with an air-cooled unit if needed. For example, an advanced turboprop might use a fuel-oil heat exchanger as the primary cooler and have a backup small air-oil cooler for ground cooling or redundancy